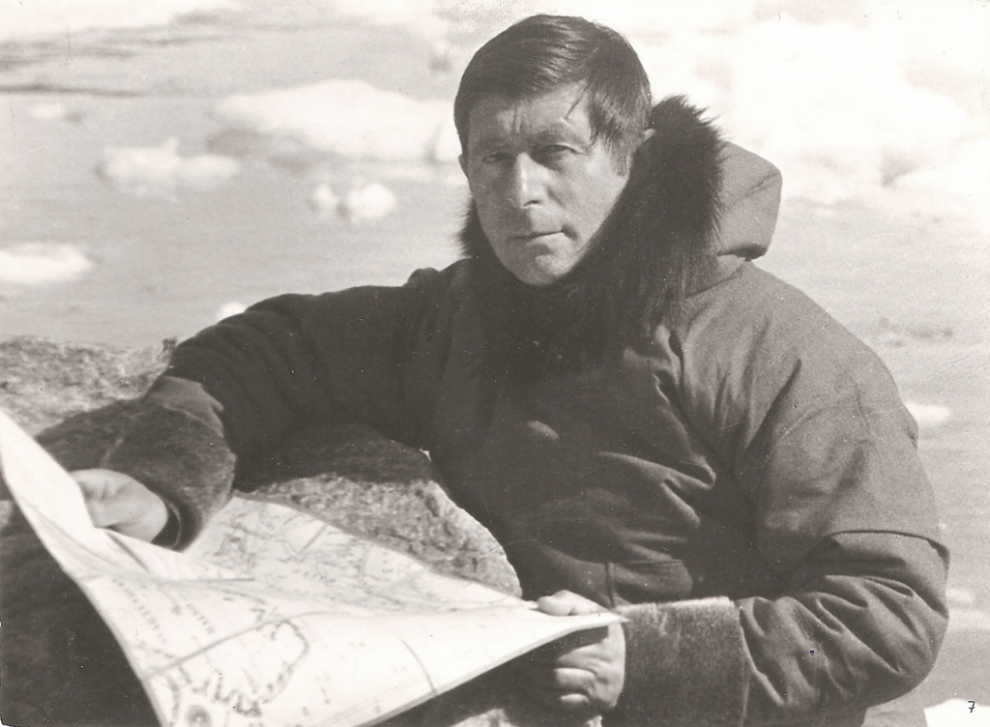

In the telegram Knud Rasmussen sent from Kotzebue announcing the success of his expedition, he included the noteworthy information, “Greenland tongue readily understood from Magnetic North Pole to Bering Strait.”

In fact, it was an understatement, for his “Greenland tongue” had served him and his companions well long before they reached the Magnetic North Pole in the territory of the Nattlingmiut — he had had little or no difficulty among the Iglulingmiut, the Aivilingmiut, or the inland Inuit of the Kivalliq.

This felicitous linguistic situation would change once he reached Nome, Alaska. Eskimos were there from all parts of Alaska to exploit the tourist season and sell curios to tourists.

This was an ideal situation in which to study Eskimo groups who had gathered from the North and the south. But it also meant Rasmussen would occasionally need the assistance of an interpreter.

His posthumous editor wrote, “Here [Nome] for the first time on all his travels round Arctic America, Dr. Rasmussen encountered linguistic difficulties.

“Wherever he had gone he had understood the dialects with very little trouble, and had also made himself understood to the natives. Now it appeared that south and west of the Yukon the dialectal differences were so great that he was unable thoroughly to discuss problems and other matters without the aid of an interpreter.”

In his own words, Rasmussen wrote: “The Eskimos from the south and west of the Yukon [River] spoke a dialect differing so considerably from the others that I found it, contrary to all previous experience, impossible to discuss difficult questions such as matters of faith and ceremonial, without the aid of an interpreter.”

The Eskimo language family is a branch of the Eskimo-Aleut family, which split into the separate languages of Eskimo and Aleut thousands of years ago. Aleut, which has several dialects, is spoken only in the Aleutian Islands and the Pribilof Islands.

The Eskimo languages, in turn, divided into two or perhaps three languages about 1,000 years ago in the estimate of linguists.

One branch is the Inuit language, spoken in Greenland, Canada and northern Alaska — a huge geographic extent. This is the area through which Rasmussen had the good fortune to travel all the way to Nome.

This language has many dialects, but neighbouring dialects are quite similar and mutually intelligible. This is known as a “dialect chain.”

The differences accumulate over distance, so that speakers of widely separated dialects may find mutual comprehension difficult or impossible.

An East Greenlander who flew from Ammassalik to Nome would find it difficult to comprehend the dialect spoken in Nome. But Rasmussen and the two Inughuit had the advantage of having travelled slowly from one dialect area to another, making maximum use of the dialect chain concept.

The other branch of the Eskimo language family is the Yupik family of languages. These languages, some of which are mutually incomprehensible, are spoken in western and south-central Alaska and also in Chukotka, a part of Russia.

The line separating the Inuit languages from Yupik is the Yukon River, which empties into the Bering Sea south of Norton Sound. (A third purported branch of Eskimo was Serenikski, spoken in and around one village in Chukotka, which became extinct in 1997.)

It is because Yupik-speakers do not call themselves Inuit that the term “Eskimo” is often used in Alaska and in discussions of Alaska — and in this article — when an overarching term is needed for the speakers of both Inuit and Yupik languages.

It is unclear when Rasmussen first formulated a plan to visit the small Eskimo population in Siberia. He wrote, “It is hard to say when I got the idea for it, for it has grown up together with me.”

The idea had been with him since 1905, when he first talked of his grand plan for an expedition to North America. At times since then, as his plans and funding requirements changed, he downplayed the idea, sometimes eliminating it completely from the plans he made public or formulated with the committee responsible for overseeing the Thule Station.

An analysis of those various plans as they had evolved over the years indicates the hope was always there.

Certainly, he harboured the idea throughout the expedition because he wrote to Ib Nyeboe, chairperson of the Thule Committee on July 29, 1921, from Greenland — after the expedition members had left Denmark, but a month before they sailed for Canada — that he would like to cross from Cape Prince of Wales in Alaska to Cape Dezhnev in Siberia.

He wrote at that time about his “strong wish to reach as far as possible all the most important areas in Alaska, inhabited by Eskimos, and — of course — in addition, a trip across the Bering Strait to the Yuits [Siberian Yupik].”

But in his telegram from Kotzebue, there is no mention of a side trip to Siberia, only that the expedition has been a success.

Travelling from Kotzebue toward Nome on the Silver Wave, off Cape Prince of Wales, he encountered Siberian Yupik visitors on their way home from trading.

He wrote, “It was a party of Siberian Eskimos from East Cape, on their way home from Teller where they had been to trade. It was a hurried meeting, but thrilling in its way, and left me more than ever keen to visit these people on their own ground.

“In the extreme eastern corner of Siberia live the most westerly of all the Eskimos, and here surely was the most fitting point at which to end the Expedition.”

Perhaps it was at that moment that he resurrected his plan to cross Bering Strait.

Source : Nunatsiaq News