Raffaello Pantucci is a senior fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore and author of “Sinostan: China’s Inadvertent Empire.”

It has been a tumultuous year for Central Asia. It started with large-scale internal violence and is ending with talk of a formal alliance between the region’s two most powerful players, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan.

Yet uncertainty remains on the horizon for the coming year, with the potential for violence to boil over, geopolitics to come crashing down around regional states or internal pressures to escalate once again.

The biggest question that still hangs in the balance is what will happen next in fellow former Soviet republic Ukraine. With little sign of an end to its conflict with Russia in sight, Central Asia will continue to find Moscow a complicated partner with which to engage over the coming year.

So far, gloomy economic predictions offered in the immediate wake of Russia’s invasion have not played out.

Higher energy prices have meant increased revenues for energy-rich Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan. Rather than falling as expected, remittances from Central Asian migrant workers in Russia have risen, thanks to a surge in demand for labor, according to the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD).

Meanwhile, Russian and Belarusian companies seeking to get around Western sanctions have set up operations in the region, as have some Western companies exiting Russia.

These trends helped prompt the EBRD to raise its 2022 gross domestic product growth forecast for the region to 4.3% in September from just 1.1% in May. It also adjusted its 2023 outlook to 4.9% from 4.7%.

It remains to be seen whether these trends can hold.

Europe’s desire to get access to Central Asian energy was on clear display during European Council President Charles Michel’s visit to the region in October. But the same fundamental problems that have long held up trans-Caspian energy routes persist and are unlikely to be resolved in the near future.

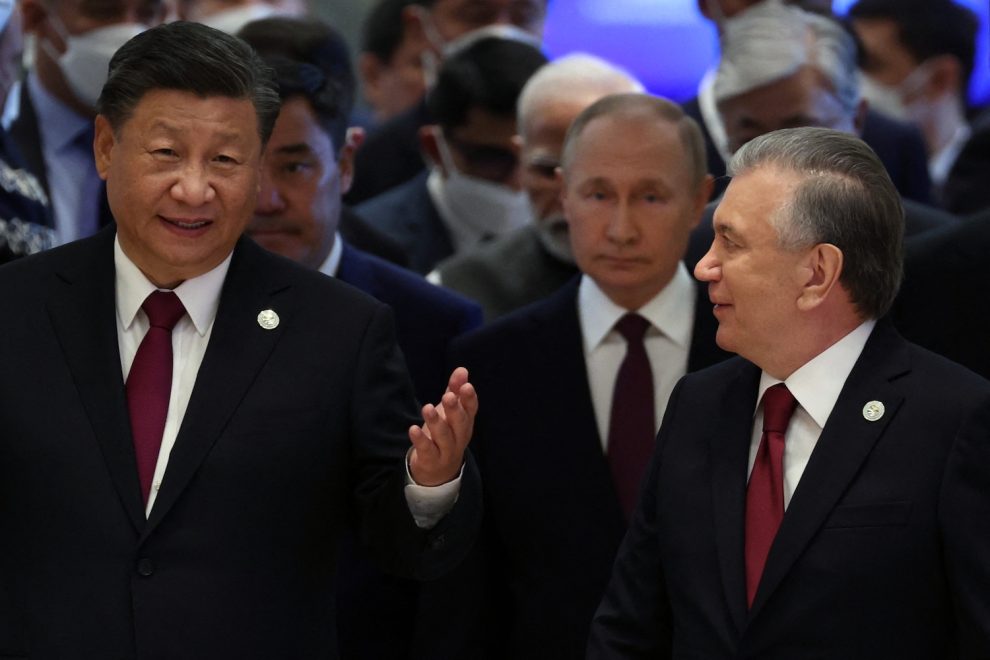

Other world leaders are courting the region, too, with Chinese President Xi Jinping choosing Central Asia for his post-COVID return to the international stage, a stream of U.S. officials coming through and Russian President Vladimir Putin taking advantage of some of the few doors around still open to him.

But despite the surge of attention and economic resilience so far, the Ukraine conflict could still carry major downsides for Central Asia.

The Russian economy could still implode, or the geopolitical balance that Central Asia has managed to strike could suddenly shift.

There has also been little international condemnation or fallout from the instability seen earlier this year in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, the continuing crackdown in Tajikistan’s Gorno-Badakhshan region or violent border clashes between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. The general attitude taken by outside powers, including the usually accusatory Western ones, is to simply move past these issues, hoping the governments will be able to handle them.

But the raft of incidents this year exposed a dangerous risk. The large-scale violence in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan was a shock to most observers. While things appear to have settled down, the unrest underscored that there are potential issues bubbling under the surface, even in the region’s traditionally more stable countries, which could lead to widespread problems.

What other surprises lie beneath the surface is of course unknown. Few, for example, would confidently speculate about what exactly is going on in Turkmenistan.

A more clear and present danger can be found across the border in Afghanistan, where the Taliban continue to exert a weak grip on power. The Islamist regime may face no direct and obvious challenger, but it is clearly unable to enforce its mandate very far.

This has particular repercussions for Central Asia, due to the continuing threat of Islamic State Khorasan as it broadcasts threats in regional languages and seeks recruits from its outposts in Afghanistan.

Led mostly by Uzbekistan, Central Asia has sought to answer Afghanistan’s problems with a push for connectivity with South Asia, but the cost of realizing this dream is prohibitively high for the countries involved to absorb themselves. International finance could help, but Taliban rule continues to pose a threat to project completion.

So far, much external engagement with the region has focused on security support for mitigating potential problems from Afghanistan, rather than large-scale transformative investment.

China remains an important partner, and the end of zero COVID might bring new economic exchanges, but it is unlikely that Beijing will be willing to expend much to realize Central-South Asian connectivity dreams.

Meanwhile, although Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan have started to make a show of strengthening their promising partnership, Putin’s proposal to join with the two Central Asian states in a “natural gas union” has not been flatly rejected.

There is a long history of grand Central Asian visions that have not managed to catch on, so it remains to be seen how these trends will play out.

The fallout from Ukraine has so far not been as bad as initially expected. And while Afghanistan remains a problem, the spillover has been limited so far.

Yet the downside risk in both cases for Central Asia remains high. The new year looks to be a challenging one.

Source : Nikkei Asia